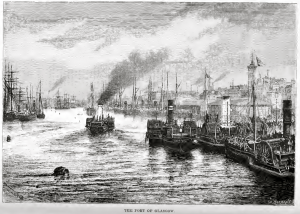

“Why, I wonder, should it feel so moving just to be here?” asks writer Peter Ross. “Well, the Clyde is not Scotland’s longest river, and it is not the most beautiful, but it is, I would say, the river which lives most vividly within the minds and imagination of the Scottish people. It carries a freight of meaning.”

And it is this very meaning that we explore in our brand new audio tour, Clydeside Promenade. Venturing along the river from Govan to Bridgeton, the tour takes in stops such as Water Row, Govan Pontoon, Broomielaw, St. Andrew’s Suspension Bridge and on through wilder reaches of Glasgow Green to the East End.

As Ross explains in his search for the source of the Clyde (in a series first written for Scotland on Sunday): “The Clyde is emblematic of what we like to believe are national characteristics – strength, rough humour, ingenuity, comradeship and a love of adventure.” But now that shipbuilding is no longer the bustling industry it once was, what role does the river play in Glasgow today?

“I think we’re a little bit uncertain what to do with it now,” says artist and University of Glasgow lecturer, Minty Donald. “It just sits there as this slightly dead waterway that’s a reminder of Glasgow’s past glories.”

Donald believes, despite its potential, we have struggled to find a new purpose for the river, “some greater use that moves beyond the river’s industrial and mercantile heritage.” Although she agrees it is a significant feature, she adds that it sits now as remnant of the past which, “is not very healthy as a symbol of the city.”

She explains, “In terms of how it affects the personality of Glasgow – if you can talk about a city having a personality – it’s not very healthy to have this reminder of something that has failed.”

However, Glasgow Humane Society Officer, George Parsonage, is more than happy to cite all the significant Clydeside developments over the years.

“There’s massive development on the river,” he beams. “Because there is no shipping, all the yards have been turned into mostly housing and hotels. We’ve got BBC and STV alongside the river. Up river we’ve got the Games Village and the new Police Scotland Glasgow Headquarters. Clyde Gateway is developing the south side at the old Shawfield Stadium. We have one new bridge and we’re getting another towards the end of the year.”

But it’s not just building developments. Parsonage is keen to address the growing trend of rowing.

“People say the river is quieter,” he explains, “but the sport of rowing is very great, upstream of the Weir. There are 400-500 boats passing through here each day – that is a lot of use of the river.

“So, although they say the river is not getting used the way it used to be, in other ways it’s getting used more.”

This human use of the river is something Donald enjoys exploring through her art. “I’m interested in that sort of push and pull between the river as a natural force – the water and the tides interacting with all these cycles that are not instigated by humans – and our attempts to try and make the river do what we want it to do,” she explains.

Although she describes it as, “a little bit lifeless,” in terms of its current role, or lack thereof, she is keen to explore and celebrate the river as a living force that cannot be tamed.

“The river is always doing its own thing and changing stuff,” she asserts. “A year ago, a part of the bank collapsed and that’s the force of the water doing its thing.

“So, no matter what we, as humans, try to do, the force of the water, the tides, the rainfall that feeds the river will work its own way, do its own thing. It will keep changing the non-watery landscape around it.”

But one change Donald would like to see is a more physical engagement between humans and the river – a wider accessibility.

“There are no places where you can get to touch the water so it’s almost being held at arm’s length from the city,” she explains. “You can walk along it and there are a few boats on it but you can’t actually get down to the water’s edge.”

Fences and railings are the main problem, Donald finds. “You can’t even lean over the water in some cases,” she explains. “They’re built in such a way that they really push you back from the water’s edge.”

But for Parsonage, who has been working at the Glasgow Humane Society since 1957, these fences and railings act as very effective safety and accident prevention methods. For someone who runs the society 24/7, almost single-handedly, these are small changes that make his daily job far easier.

“It’s always good when you rescue someone but then you have to think, ‘Why are they in the water?’,” he says. “There’s a part down river where there used to be no fence and we had dozens of people fall in there. I’ve rescued dozens of people there and I’ve taken a fair number of bodies of the people who drowned there. But now, driving past it, I’ve got to smile because there’s a lovely fence there that stops people falling in.

“We worked hard to get that fence, it’s a success story. The people can sit on the grass and picnic right next to the river but there’s a fence to stop them falling in or doing something silly. I think that’s the biggest reward.”

For Parsonage, enjoying the river at ‘arm’s length’ isn’t something that should be questioned so much as celebrated, for all concerned.

Another issue is, of course, the quality of the water itself. The Clyde is still one of the most heavily polluted water courses in Britain and, with raw sewage being dumped into the river on a regular basis, it has become, what Donald describes as a ‘toxic soup’.

“It’s not conducive to human use,” she says. “But it’s not just for humans. It seems to be supporting a lot of wildlife like worms and slugs that really love the toxic soup that the river is at the moment.”

She hopes to see the city invest in a sewage treatment system so it could become, “a waterway that we could get down to and even swim in, if the weather was ever nice enough.”

This is one area in which Donald and Parsonage can find some consensus. “I keep tormenting SEPA that they don’t clean the water, God does,” jokes Parsonage. “It’s only good rain that’s going into the river and if we stop putting the muck in, it’ll gradually become clean again.”

Returning to Peter Ross’s poetic description of the river, “From the waterfall, it will pass through the industrial heartland, bisect the city, then flow out to the coast. The end of that 100 mile journey – the towns and islands of the Firth – has long been associated with pleasure. But to witness the beginning of the river’s journey is, above all, a privilege.”

And it is our privilege at Walking Heads to present our Clydeside Promenade audio tour, as part of the Culture 2014 programme.

Part One is now available for free on iTunes. Download Clydeside Promenade directly from our GuidiGO page by clicking HERE.

Let us know how you are getting on. Send us your photos and updates on Facebook and Twitter (use the hashtag #ClydeProm).

Parts Two, Three and Four to follow soon.

Leave A Comment