A gateway opens. Where does it lead? To a wider world? To inspiring people in unexpected places? To be honest right now I have no idea, but I’m tentatively opening the gate….

Why?

Pop music is a gateway to a wider world… So I’m really hoping this will have a ripple effect. It’s a fantastic year for local popular culture. With this exhibition and hopefully the V&A in Dundee taking off. What we’re doing is bringing stuff that’s more relevant to everyday lives into the wider cultural domain.

Stephen Allen, curator Rip It Up.

It’s a great adventure for a new year. To go exploring. In search of museums – perhaps lesser known ones, in tucked away places – with treasures to delight and stories to surprise. I’m newly curious to know more about the connections between local museums and local artists, and how that might relate to the development of personal identity and sense of place. Whether it is part of an interconnected national network? Maybe this also links to the campaign to make museums in general more ‘relevant’ to daily life and engage with wider audiences?

The idea comes from a chat with Stephen Allen, curator of the National Museum of Scotland’s rock n roll exhibition Rip It Up. Before it opened Amanda Mitchell and I recorded a WalkingHeads Talking Feet podcast conversation in a noisy corner of the crowded museum café.

Listening to the podcast, you can hear babies crying, mobile phones ringing, cups clinking and the crazy millennium clock chiming the quarter hours.

That’s the sound of modern museum life. Or part of it. Keep listening and you hear Stephen Allen’s ambition for the Rip It Up exhibition he was just bringing to fruition. Before the doors opened, he was hoping it would start a ripple throughout Scotland. In an age of nostalgia he expected it would touch a chord with visitors.

He hadn’t expected quite such an emotional response:

The comments book is quite striking, as well as emails I’ve had. Even many of the criticisms of omissions have been couched with “but I really enjoyed the exhibition). Gratifyingly feedback from many of the participant artists was very positive.

Stephen Allen

Open Up Museums

Making museums more relevant to everyday life is not a new idea. It’s been gathering pace throughout the 21st century, not least with the Open Up Museums project across the UK initiated by the Association of Independent Museums (AIM) in 2017.

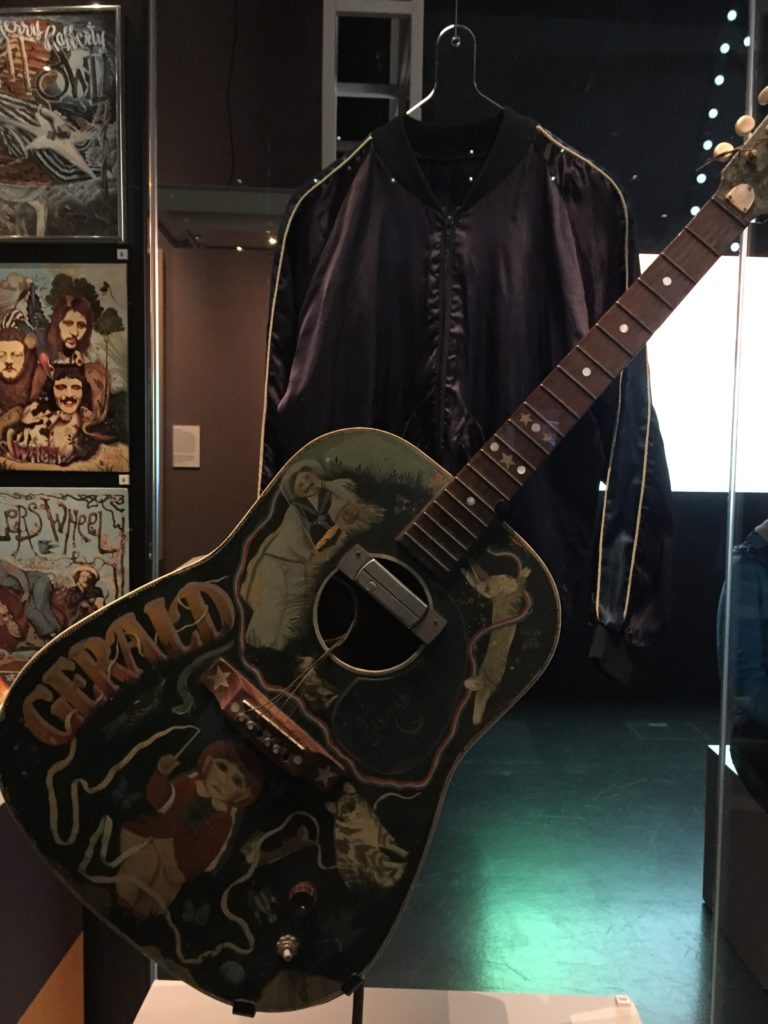

Yet, doing it with pop music was a brave step for the National Museum of Scotland. Rip It Up depended on a different kind of archive; personal memorabilia – costumes, photographs, instruments, ticket stubs, set lists, 30 year old copies of NME – borrowed from attics and basements of fans, artists and venues. And, I think, not a little of the personal investment of the chief curator. Stephen Allen, a Rezillos fan, who spent the last three years of his life deeply immersed in the minutiae of Scottish pop history, confesses it was Siouxsie and the Banshees who first fired his interest in Weimar Germany.

His time and effort paid off. The exhibition was a rip roaring success, attracting enthusiastic reviews, and around 52,000 people of all ages to a tightly packed trip along 60 years of Scottish rock n roll. Music and film were essential elements. But the audience was also a vital part of the atmosphere in an exhibition which was carefully designed to be a social experience. ‘We deliberately chose not to put visitors in headphones,’ says Stephen.

Rip It Up admittedly avoids the complacent, self-congratulatory attitude that now prevails almost everywhere within the Scottish arts. Its curator is a Liverpudlian who has cultivated an encyclopaedic knowledge about Scottish music.

Nostalgia not just for baby boomers

If pop culture can open a wider world for the audience, can it also open museums to a wider audience?

On my visit to the exhibition, on a grey November Saturday afternoon, I encountered a kind of energy you don’t often find in museums. I was intrigued to see how many people of different ages were clustered round each screen and showcase. Feet tapping, mobile cameras clicking. From Lonnie Donegan to Young Fathers, it seems that memory lane can weave an elastically long or short route through Scottish culture. Nostalgia is not just for baby boomers. At times, working through the crowds it felt like time-travelling a series of mini rock festivals. But without the mud. And much better toilets.

So a gateway opened. But who went through it? Just looking around, there was no way of telling how many people were regular or first-time museum visitors. The NMS is rightly proud of drawing at the last count 2.3 million visitors each year (more than Edinburgh Castle). But while Stephen Allen waits for a more detailed demographic breakdown of the Rip It Up audience (adult tickets £9) there is a wider debate over the social reach of museums, galleries, theatres – the arts in general.

Music tends to appeal to a wider audience. Or, to put it differently, live music events are likely to bring together a diverse mix of people who might otherwise not meet in the same place at the same time. As Tony Walsh puts it in his deeply moving poem, We Are Manchester

It’s where we come together for those moments that we share

It’s twenty thousand people with our arms held in the air

It’s songs that sing a truth to us and nothing but the truth

It’s twenty thousand spirits raised enough to raise the roof

The democratic museum?

No wonder Rip It Up stirred emotions. Which is exactly what reforming campaigners say museums should be doing. (Read this sizzling blog series on the democratic museum by David Fleming Professor of Public History at Liverpool Hope University, former Director of National Museums Liverpool and president of the Museums Association.)

Inevitably, given the emotions, it’s impossible to please everyone. Rip It Up also stirred disappointment. ‘We had comments and criticism about certain omissions or not representing as fully as we might (eg Blue Nile, Cocteau Twins, some of the 60s-70s early bands…”

To which, Stephen Allen’s best answer is: Go to your local museum, develop a local history society around the subject, get people involved, start collecting…

Well, what are we waiting for? What better time could there be to explore the myriad ineffable influences of personal, local and national identities. I’m now contacting museum guides and curators to help me plot a route map into the (to me anyway) unknown. I might be some time, but I’ll be reporting back as often as I can.

Listen HERE to Stephen Allen in conversation with Jonathan Trew of Edinburgh Music Tour (also delving with oomph and enthusiasm into unexpected stories of the capital city). Walking Heads Talking Feet podcasts are available on iTunes and all your usual platforms. [We also do pretty good audio walking tours of Glasgow music and other cultural scenes.]

This post is by Fay Young, Walking Heads research and development director. It is also published on Sceptical Scot

Featured image is from Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Little Sparta: Picture Fay Young

Leave A Comment