Tread softly on the way to Paisley Town Hall; it’s a journey threaded with names of the stuff that made a great civic centre. Here’s Gauze Street crossing the canal. Turn right at Abbey Place just before the road divides between Lawn Street and Cotton Street. And pause.

I’m a little late for a day’s conference celebrating the difference people make to places. But this is my first visit to Paisley in a long time – perhaps the first time ever in daylight – and it’s not what I expected. What’s the surprise? Not the grand buildings. In all of Scotland only Edinburgh has more listed buildings than Paisley. But Edinburgh’s city centre streets tend to celebrate royals and rogues (Henry Dundas, for example). Here grand buildings occupy streets named for the people whose labour made the wealth – and how they did it.

Surely not many town centres map their heritage with such evocative precision? Wander on and you’ll find Lacy, Silk and Thread Streets, roads for Spinners, Spoolers and Weavers, and Bobbin and Shuttle streets too.

Founded on philanthropy

‘Paisley has two great origins: the church and the textile industry,’ says Alasdair Morrison, pointing to the 850 year old Abbey in front of us then over towards the more distant but equally impressive (and listed) Anchor Mill. All around us, symbols of a splendid past, monuments to an era when Paisley was at the centre of an industrial empire. At one point the mills were producing 90 per cent of the world’s thread.

Those days are gone. ‘The lights went out 25 years ago,’ says Alasdair Morrison. A long decline followed closure of the last of the cotton mills in 1993. But the head of regeneration for Paisley is not downhearted. Today, the first cloudy day of a sparklingly sunny May, he sees plenty of reasons to be cheerful.

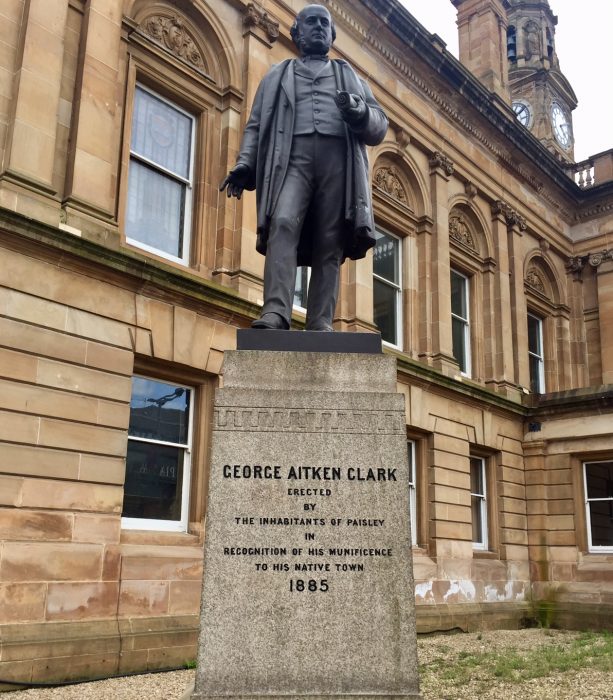

Alasdair Morrison is leading a mini tour of Paisley during an upbeat event in the imposing Victorian town hall right behind us. ‘Paisley is founded on philanthropy,’ he adds. The civic grandeur is a legacy of 19th century thread-rich philanthropists like George Aitken Clark whose ‘munificence’ is recognised in the statue next to the town hall.

In 21st century Scotland, resources of renewal are found elsewhere. Today we’re here to learn how communities are transforming town centres – with the right amount of support from public bodies and private enterprise.

A nation of towns

There is probably no better location for, Seeding Success, Learning from Stalled Spaces Scotland. Hosted by Architecture and Design Scotland, it demonstrates how communities can bring derelict and disused spaces back to life. After all, Paisley’s bid for UK City of Culture 2021 aims to build on the community pride increasingly evident at events like the four-day food and beer festival which filled the public space between the town hall and the abbey in April. ‘Top down simply doesn’t work,’ Alasdair Moffat had told us outside.

Stalled Spaces Scotland, a national project commissioned by the Scottish Government, took inspiration from the Glasgow Stalled Spaces programme to transform those under-used green spaces that blight so many town centres. Confounding some initial scepticism it has fired imaginations in all kinds of places.

A strip of land next to a railway embankment in Paisley just a metre wide is now a wild flower meadow: Susan Mansfield Stalled Spaces background

Inside the town hall, the day is full of inspiring stories demonstrating just what can happen when communities get stuck in. Here’s a table learning about the pop up cinema on the waterfront of Kirkcaldy (like many towns it usually turns its back on the best views) where Jaws thrilled the crowd so much they forgot the blistering cold summer winds. Elsewhere there’s talk of community gardens and green gyms, exhibitions and street theatre, murals and wildflowers bringing life to wasteland waiting for development. And lots more opportunities for the future.

What is wasteland? Panel speakers urge the end of dereliction. ‘We should remove dereliction from town centres,’ says Phil Prentice from Scotland’s Towns Partnership. But also agree with Sue Evans of the Central Scotland Green Network, that dereliction can inspire imaginative reinvention. [Regeneration is bringing new life to derelict listed buildings in Paisley]

There’s more inspiration in the quirky collaborations between Copenhagen and Edinburgh in the City Link Festivals – described by Carol Hayes of Givrum – bringing together creative souls from the two capitals with like minds in Barcelona and Istanbul.

But creative energy is not confined to cities. ’Scotland is a nation of towns, and Paisley is Scotland’s largest town,’ stresses Phil Prentice. Stalled Spaces funded community groups in fifty towns in seven local authorities across Scotland, from Ardrossan to Cupar, from Oban to Montrose.

Who owns the town centre?

No-one pretends it is easy. The Stalled Spaces toolkit gives detailed advice on the careful planning and sheer determination needed for success. And there are obstacles to overcome. Community groups may need encouragement to get involved in town centre projects.

‘But isn’t that a council responsibility?’ was a common first reaction. Once engaged, it might be hard to let go: a much-loved local pop-up might not want to pop down again, which could deter property owners from making empty space available for community use. Success depends on making sure all parties understand the project is temporary.

At the end of the day Stalled Spaces Scotland is regarded as an inspiring success. So successful it begs a new question, tweeted by @SGP (Sustainable Glasgow Project):

So, why is #StalledSpaces ending? It’s ok seeding new ideas but why finish the project if it’s such a success? #seedingsuccess @ArcDesSco

And a quick response on stage from Diarmaid Lawlor, A&DS Director of Place, affirming that it’s not the end, it’s an evolving process. The seeding, supporting, sharing and learning will continue.

Outside, as we leave the hall, the sun has emerged, shining on the Abbey, lighting up the Arnotts building on Gauze Street. B listed and formerly derelict, the old department store is about to be reinvented as the 120 seater Cardosi restaurant.

Not for the first time a comparison with Dundee springs to mind. In Paisley, as in Dundee, a new optimism is re-shaping the post-industrial landscape. The energy, imagination and enthusiasm of local people – so evident in Seeding Success – was an essential element of Dundee’s successful bid for UNESCO City of Design.

Can Paisley become UK City of Culture 2021? There’s an infectious confidence in the air.

‘Yes,’ asserts the Twitter profile of Jean Cameron project director of Paisley 2021, ‘we know we’re Scotland’s largest town and not a city. That works for UK CoC bid’.

Somehow, as I thread my way back to Gilmour Street Station, that sounds like the template for a new Paisley pattern.

Featured image: Commonwealth Youth Circus, Paisley: Stuart Crawford, Creative Commons license CC By -NC-ND 2.0

Article by Fay Young, research and development director of Walking Heads

Leave A Comment